There is a crisis of creativity in advertising. You have probably heard these very words or a variation in the past few years. Campaigns striving to touch on the same key points, unoriginal tropes used over and over again – things are starting to look quite boring, aren’t they?

But occasionally a pearl shines through the mud and delivers some unprecedented creative drive and energy. How does that work? How do you wade through the noise and an increasing desire for standardised, massificated content?

With these questions in mind, we reached out to Mike Campbell, head of international effectiveness at Ebiquity, who was keen to share his opinions on the topic below.

Advertising is facing a crisis in creativity that means many brands are failing to secure meaningful return on advertising investment. It matters, because creative has been shown to be the single most important driver of advertising effectiveness. In a 2017 analysis of nearly 500 campaigns, Nielsen found that creative contributed 47% of total sales, the most of any element, followed by reach (22%), brand (15%), and targeting (9%).[1]

The crisis in creative effectiveness was serious six months ago; in the wake of the global coronavirus pandemic it is doubly so.

How did we get here?

There are several factors underpinning the crisis in creative effectiveness. For more than a decade, repeated studies by Peter Binet and Les Field have shown that the optimal balance of investment requires brand teams to allocate around 60% of ad spend on long-term, brand building activity and around 40% in short-term sales activation. Brand building is designed to sustain brands via long-term sales growth, with its impact measured for years and effects lasting more than six months. Sales activation, meantime, is designed to drive behaviour in response to direct calls to action, with impact measured over weeks and months – and even days and hours in some cases.

Different categories benefit from different investment ratios, but a 60/40 split is a good rule of thumb. Binet and Field’s research since the mid-2000s has found this ratio holds good today, despite constant innovation in the increasingly-digital advertising ecosystem. It also reflects our own analyses since 2010, captured in the Ebiquity effectiveness databank.

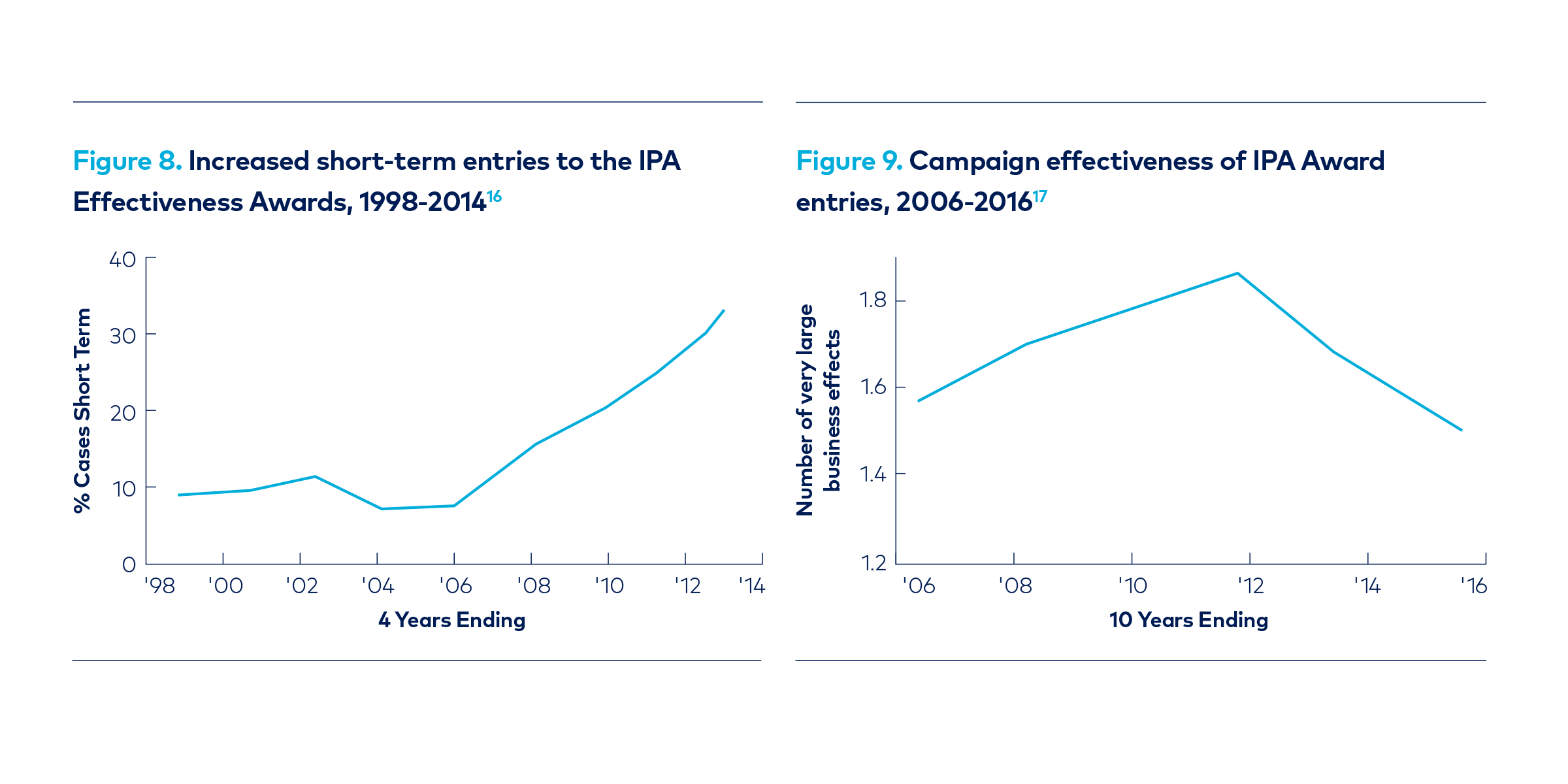

Binet and Field characterise the 2010s as the decade in which advertisers deviated from the 60/40 rule and piled investment into short-term sales activation. This was evident in the increased number of short-term entries to the IPA Effectiveness Awards in the 16 years to 2014, as shown in Figure 1. Their analysis of campaign effectiveness over the same period recorded a very rapid decrease in very large business effects generated by advertising, particularly since 2012, as seen in Figure 2. As Field memorably has said: “The more we move towards real-time, the more we move towards deal-time, and this is harming brands’ profitability.”

Figure 8. Increased short-term entries to the IPA Effectiveness Awards, 1998-2014 [2]

Figure 8. Increased short-term entries to the IPA Effectiveness Awards, 1998-2014 [2]

Figure 9. Campaign effectiveness of IPA Award entries, 2006-16 [3]

Two factors have fuelled short-termism at the expense of long-term brand building. The first is the rush to digital, with the advent and rapid growth to dominance of online advertising platforms, from Facebook to Instagram, Twitter to Tik Tok. Fear of missing out and a misperception that “everyone else is doing it”, combined with the readily-available metrics generated by digital, led many advertisers to invest suspiciously-round, untested percentages of their budgets in digital media – 30, 40, 50% or more. This online ad goldrush was further propelled by a second factor: agencies encouraging their clients to invest, based on attribution models that purported to demonstrate the impact of these new channels.

Flawed digital attribution models

I have sat in too many meetings in which media agency planning directors forcefully championed the latest – often their own, proprietary – digital attribution model, without understanding from their insights colleagues how they worked or what they showed. The fundamental flaw in most of these models is that they completely fail to measure incrementality. By assigning credit, often arbitrarily, to touchpoints along the customer path to purchase – often the first or last click – the models assume that it is their favoured touchpoint that is responsible for generating sales. But that isn’t what the data shows.

What’s more, almost every digital attribution model I’ve ever analysed fails to account for other critical factors, such as: base sales, momentum of sales performance, seasonality, competitor activity, and often – stunningly – broadcast media. By design, these models automatically overstate the impact and importance of digital media.

In the last couple of years, the digital attribution market has crashed because it has become impossible to source the log-file data that fuels it, coupled with the walled gardens, GDPR, and the death of the multi-site cookie. This may yet turn out to be a significant positive, particularly if digital media goes on to rely on properly-understood analytical techniques that scale digital media’s effects correctly. In the meantime, advertisers have invested billions of dollars in short-term sales activation that can’t be shown to work – and at the expense of long-term brand building.

Siloed thinking

Over-investment in short-term sales activation has another antecedent, too. Despite the fact that digital marketing is now into its third decade, many companies still suffer from siloed marketing structures. Businesses born digital don’t have this challenge, but many of the world’s leading brands still keep marketing and ecommerce separate. Moving to a measurement framework which accurately reports on the real-world impact of the totality of marketing investment across channels would not be in the interests of the ecommerce team. This is because it would often deflate the ROI generated by digital sales activation tactics and lead the budget allocated to them to be cut and returned to brand building.

The constituent elements of creativity

In long-term brand building, the constituent elements of creativity are known as distinctive brand assets. A collection of these assets are known as a fluent device.

Distinctive brand assets are the attributes associated with a brand that, through sustained association over years, build long-term memory structures in consumers’ minds. Constant pairing of the asset and the brand build both familiarity and likeability. Assets can be visual (logos, fonts, colours, shapes), verbal (brand and product names, ownable brand language), and auditory (sonic branding, from the Intel Inside jingle to the 20th Century Fox fanfare).

A fluent device is higher order collection of distinctive brand assets, presented as a strapline or a character. One of the leading creative research companies, System 1 Group, defines fluent devices as “a creative conceit (slogan or character) that is used as the primary vehicle for the drama of a long-running campaign”.[4] Fluent device characters include: Aleksandr Meerkat (Compare the Market), Tony the Tiger (Frosties), and the Lloyds Bank black horse. Famous fluent device slogans include: “Have a break, have a Kit Kat”, “Every little helps” (Tesco), and “I’m lovin’ it” (McDonalds).

COVID considerations

The coronavirus pandemic has changed many things – in the world and in marketing – but it has not changed the rules of how to build and sustain brands. Distinctive brand assets and fluent devices – which serve to set brands apart from each other – still really matter. Yet in two waves – first “we’re all in this together” and then the “shot on iPhone” ads – too much of recent advertising has been too similar. Some brands – including Tesco and BA – have creatively redeployed their existing assets and devices for the new environment, with Tesco flexing “Every little helps” by giving NHS workers and over-70s priority access to their stores, and BA using its established visual and sonic devices to report on its bringing both stranded citizens and much-needed PPE (back) to the U.K.

Summing up

Clearly, when many sectors and businesses are under extreme financial pressure – with CFOs chasing cash just to pay salaries and rent – it’s tempting for brands to try to drive short-term sales. But what advertising since the 2007/8 financial crisis and through the digital boom of the 2010s have clearly shown is that over-investing in short-term sales activation at the expense of long-term brand building is fool’s gold. Getting the balance right is what will be key to recovery and growth, and for many brands – dark for three months or more and about to enter the deepest recession in living memory – the pandemic does at least provide the opportunity for a hard reset.

Read the full article in Creativepool, here.

First featured 03/08/2020.

[1] Nielsen (2017). “When it comes to advertising effectiveness, what is key?”, http://bit.ly/35TSXju

[2] Les Binet & Peter Field (2016). Selling creativity short, WARC Webinar, http://bit.ly/2MDoSgS

[3] Les Binet & Peter Field (2018). Media in focus: Marketing effectiveness in the digital era, IPA, http://bit.ly/2lIPXUB

[4] Tom Ewing (2017). “Fluent Devices and the forgotten art of memorability”, WARC Webinar, http://bit.ly/2XoAera